Daphnia

TYPICAL COLOUR CHANGES THROUGHOUT THE YEAR

Often a White or Pale Yellow during the colder months, changing to an Olive Green in the summer, which on closer inspection can appear more of a Brown-Pinky-Orange mixture.

JAN

JUNE/JULY

DEC

From regular examination of stomach contents, we know that daphnia (or ‘water fleas’) are one of the most common foods of Walthamstow trout, probably outnumbering even buzzers in their frequency.

Source: Functional Genomics Thickens the Biological Plot. Gewin V, PLoS Biology Vol. 3/6/2005, e219.

The life cycle of daphnia is fascinating, and an aspect that has rarely been touched by fly-fishing writers. Life span is usually about ten to thirty days, and is largely dependent on temperature, with individuals living longer at lower temperatures than they do at higher.

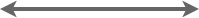

Its method of reproduction appears to have evolved to make the best use of environmental conditions in as short a time as possible. During spring, summer and autumn, daphnia reproduce asexually, with females bearing live young without fertilization by males which may be absent during these periods.

An average of ten embryos are nurtured in the brood pouch inside the shell, and are hatched in around two days when the female moults and discards the old shell. These are clones – exact genetic replicas of the parent – and once hatched must moult several times before they are fully grown, a process that varies from six to ten days.

Under ideal conditions these fully mature females are able to produce a new brood of young – also female – about every ten days. Such a ‘daphnia bloom’ continues while environmental conditions support their growth, although there can be ‘pulses’ of population growth throughout the year.

Once environmental conditions become harsh – in drought, conditions of overcrowding, accumulation of waste, lower food availability, or with the approach of winter – some embryos develop into males, while females begin to develop eggs which need to be fertilised.

Daphnia containing the darker

saddle-shaped ‘resting egg’.

Source: Daphnies; Thomas Bresson

(These 1-2mm cases may be the gritty little objects about the size of poppy seeds which suddenly seem to be in every piece of weed you pull in at certain times of the year.)

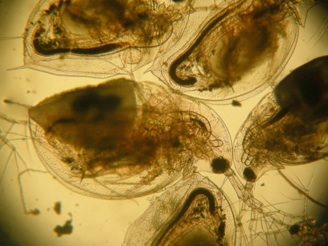

Saddle-shaped ‘resting egg’ and the

juvenile Daphnid that just hatched from it.

Source: Sarah Bandoni & H. MacIsaac University of Windsor

Another colouration factor is apparently conditions of high temperatures and low oxygen availability, which causes it to develop more haemoglobin and give it a pink or reddish appearance. In oxygen-rich conditions (as in the colder temperatures of winter) it takes on a yellow or un-pigmented - white - appearance.

50% protein and 20-27% fat, daphnia are a nutritious food, and Walthamstow regulars believe that a trout does not taste like it should until it has had a chance to lose the oily fishmeal taste of the pellets it was reared on, and had a good few weeks of decent daphnia feeding. In some years it’s been known for Walthamstow trout to develop an almost prawn or shrimp-like flavour from this rich micro-crustacean diet.

Experiments have shown that trout prefer to feed on larger daphnia and individuals which are pigmented rather than colourless, presumably because they’re bigger, easier to see and give a better return for energy exerted. Daphnia have also been seen to decrease their size when levels of adult fish population are high, and increase it when there is a prevalence of juvenile fish, both measures to avoid being eaten.

It’s a common sight at Walthamstow and other fisheries to see fish movement near the surface towards evening but with very little insect life coming off. Stomach contents of caught fish reveal them to have been feeding on daphnia. This upward movement of daphnia in response to lowering light levels is part of a daily vertical movement up and down. At other times, research has shown daphnia moving towards increased light instead of away from it. It is also believed this movement to a lower depth during the day may be an attempt to avoid predation by fish.